As the world gets bigger, we’re starting to understand just how complex life is. Unless we seek atrophy by feeding it a consistent junk food of disposable television, our brains should become increasingly better with experience at making connections between seemingly unrelated topics.

Take assessing human behaviour for example. Look long enough and you’ll start to understand how others will react to events. Or how they’ll misjudge situations for any number of reasons. Some people call it wisdom. Or experience. But whatever it is, there’s no doubt it’s easier to identify in others – we recognise patterns taking shape once they become prominent because we noticed them in the first place (the red car, or Baader-Meinhoff, phenomenon).

Of course, you’re likely to suffer from similar flaws yourself. It’s just that we all have terrible eyesight when it comes to identifying our own behavioural prejudices, making them much easier to identify in others.

Someone (Einstein? if not, perhaps Mark Twain – since most internet quotations tend to get attributed to him by default if there’s any doubt as to its provenance…) once said:

“The more I learn, the less I understand”

Things are complex. As Tyler Cowen is fond of saying, he’s not hugely enthusiastic about space exploration – because there’s so much vast untapped potential still to explore here on earth that could bring more immediate benefits for humanity (initially in the oceans which to this day remain undiscovered territory).

But as we start to travel more freely (and quickly) and communicate near-instantly around our global village, one thing that’s becoming clear is that so much of the research that we’ve been carrying out into what makes humans tick is fundamentally flawed – because we keep using a very small group of humans in our scientific research. To put it another way, most of those test individuals are WEIRD – Western, educated, industrialised, rich and democratic. And most of the people in the world are not like that:

“more than 90 percent of studies recently published in psychological science’s flagship journal come from countries representing less than 15 percent of the world’s population.”

For example, in carrying out a simple pattern recognition test on children in Zambia, it turned out that they scored way below those in the West on identifying the missing item in a row of simple two-dimensional shapes (squares, triangles etc). Yet in a repeat test using more familiar three-dimensional shapes (stones, toothpicks etc), those figures changed significantly for the better.

The research was flawed because the context was wrong.

In other words, there seem to be some fairly significant misplaced presumptions about what constitutes ‘normal’ when it comes to human behaviour. We’re only now starting to realise that this is the case – so I think it’s safe to assume that there are going to be some pretty different and surprising test results that arise in experiments around human behaviour over the next few decades as the net gets cast far more widely and we expand the focus of our research considerably.

We’re all humans. And maybe we’re all very similar. But if it turns out that we’re not and you’re reading this blog today, it’s good to remember – you’re probably one of the weird ones.

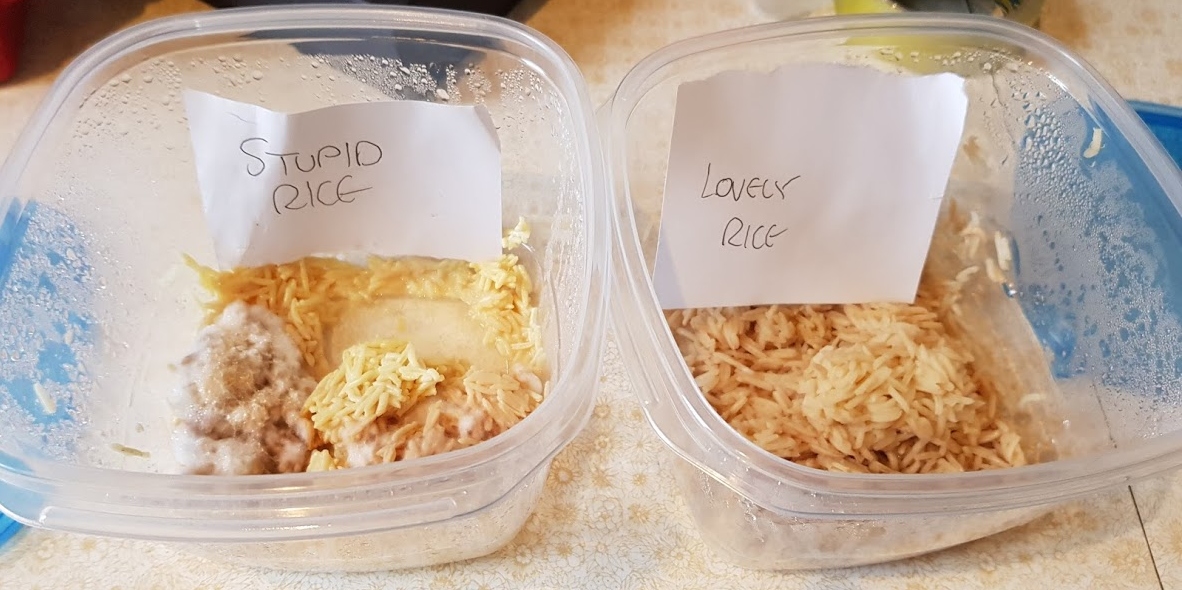

You’ll just have to take my word for it. But the rice that got abuse for a month? Ended up in a pretty bad shape. Whilst the other was almost the same as the day it went into the container.

You’ll just have to take my word for it. But the rice that got abuse for a month? Ended up in a pretty bad shape. Whilst the other was almost the same as the day it went into the container.